미국 존스홉킨스대 연구진이 로봇 손이 통증까지 감지하도록 하는 전자 피부를 개발했다. 이를 통해 장애인은 로봇 손을 실제 손과 같이 느낄 수 있으며, 또한 로봇 손이 위험에 처하는 것을 바로 감지해 회피할 수 있다.

미 존스홉킨스대 존스홉킨스대의 엔지니어들이 전자 피부를 개발해 로봇 손의 손가락 끝을 통해 촉감을 회복하는 것을 목표로 하고 있다.

사진 홈페이지캡쳐

28일 존스홉킨스대 학술 홈페이지(원문을 보려면 https://hub.jhu.edu/2018/06/20/e-dermis-prosthetic-sense-of-touch)에 따르면 손발을 절단하는 수술을 받은 사람들은 종종 잃어버린 신체 일부가 아직도 그 자리에 있는 듯한 ‘환상지(幻想肢)’ 감각을 경험한다.

그런 감각의 착각이 존스홉킨스대 엔지니어들이 개발한 전자 피부 덕분에 거의 실제 감각으로 구현될 수 있게 됐다. 이 전자 피부(e-dermis)는 로봇 의수(義手) 맨 끝에서 손가락 끝에 오는 실제 촉감을 다시 되돌려줄 수 있다.

이번 연구에 참가한 장애인은 “마치 빈 껍질이 생명으로 다시 채워지는 것처럼 몇 년 만에 내 손의 감각을 느꼈다”고 말했다(이번 연구 규정상 실험에 참가한 장애인의 신원을 밝힐 수 없다).

전자 피부는 천과 고무 사이에 센서를 달아 신경 말단을 모방했다. 이를 통해 촉감뿐 아니라 통증까지도 감지해 말초 신경으로 전달한다.

생명의학공학과의 대학원생인 루크 오스본 연구원은 “우리는 손가락 끝을 감싸는 센서를 만들어 실제 피부처럼 작동하도록 했다”며 “촉감과 통증 모두를 감지하는 인체 감각 수용체에서 일어나는 일에서 영감을 얻었다”고 말했다.

또 오스본 연구원은 “시판 중인 로봇 손에 전자 피부를 장착함으로써 장애인이 로봇 손의 손가락으로 집고 있는 물체가 둥근지 아니면 끝이 날카로운지 알 수 있게 했다는 점에서 흥미롭고 새로운 연구”라고 덧붙였다.

국제학술지 ‘사이언스 로보틱스’에 실린 이번 연구결과는 로봇 의수를 사용하는 장애인들이 촉감에 바탕을 둔 자연스러운 감각을 다시 회복할 수 있음을 보여준다. 통증을 감지할 수 있는 능력도 예를 들어 로봇 의수나 의족에 미칠 수 있는 잠재적인 피해를 경고할 수 있어 도움이 된다.

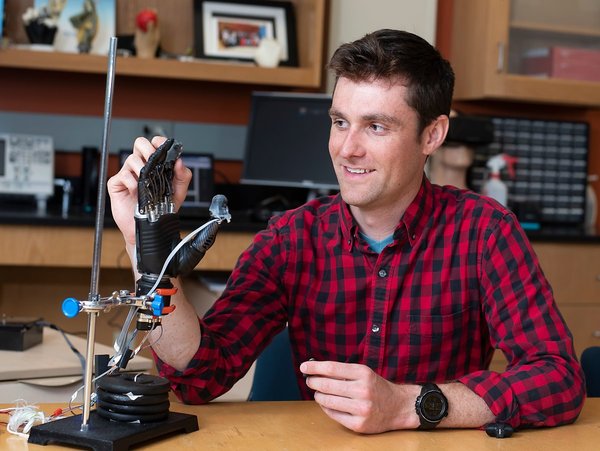

미 존스홉킨스대 대학원생 루크 오스본 연구원이 전자 피부가 장착된 로봇 손을 만지고 있다. 사진 홈페이지 캡쳐

인간의 피부는 뇌로 다양한 감각을 전달하는 신경 수용체들의 복잡한 네트워크로 구성돼 있다. 이 네트워크는 존스홉킨스대 생명의학공학과과 전기컴퓨터공학과, 신경학과, 싱가포르 신경공학연구소 과학자들로 구성된 연구진에게 생물학적 모델을 제공했다.

오스본 연구원은 “최신 로봇 의수 설계에 인간의 감각을 더 많이 구현하는 것은 특히 통증을 인지하는 능력을 포함시킬 때 중요하다”고 말했다.

오스본 연구원은 “물론 통증은 불쾌하지만 이 또한 시중의 로봇 손에는 없는 핵심적인 신체 보호용 촉감”이라며 “로봇 손의 설계와 통제 메커니즘의 발달을 통해 장애인이 잃어버린 기능을 회복할 수 있지만 종종 중요한 촉감이 누락된다”고 말했다.

전자 피부는 바로 그런 곳에 필요하다. 장애인의 팔에 있는 말초신경을 자극해 촉감 정보를 전달함으로써 이른바 ‘환상지’를 실제 감각으로 만든다. 인체에서 일어나는 생물학에서 영감을 얻은 전자 피부는 사용자들이 가벼운 접촉에서 불쾌하고 아픈 자극까지 다양한 촉감들을 감지할 수 있게 해준다.

이번 논문의 대표 저자인 존스홉킨스대 생명의학공학과의 니티시 타코르 교수는 “전자 피부는 장애인의 피부를 통해 신경으로 전기 자극을 줘 인체에 전혀 손상을 주지 않고 이와 같은 촉감을 구현한다”고 말했다

타코르 교수는 “처음으로 로봇 손이 아주 미세한 접촉에서 불편한 감각까지 전달함으로써 실제 사람 손과 흡사해졌다”고 말했다. 그는 이번 연구에서 사용한 로봇 손을 제공한 볼티모어의 인피니트 바이오메디컬 테크놀러지의 공동 창업자이다.

연구진은 인간 신경 시스템의 촉감과 통증 수용체를 본뜬 ‘신경모방 모델’을 만들어 전자 피부가 실제 피부처럼 감각을 전기신호로 만들게 했다. 연구진은 뇌파 측정을 통해 실험에 참가한 장애인이 전자 피부를 단 로봇 손을 통해 수술로 절단한 손이 아직도 있는 것처럼 느낀다는 것을 확인했다.

연구진은 인체에 손상을 주지 않는 ‘경피 신경 전기 자극(TEN)’을 통해 실험 참가자에게 전자 피부에서 나오는 신호를 연결했다. 연구진은 통증 감각 실험에서 장애인과 로봇 손이 끝이 뾰족한 물체와 접촉할 때 오는 통증이나 둥근 물체를 만질 때의 일반적인 촉감 모두에 대해 자연스러운 반사 반응을 경험하는 것을 확인했다.

이번 연구에서 개발한 전자 피부는 온도는 감지하지 못한다. 연구진은 물체의 굴곡(촉감과 형태 인지용)과 날카로움(통증 인지용)을 감지하는 데 집중했다. 오스본 연구원은 전자 피부 기술은 로봇 시스템을 보다 인간과 흡사하게 만들 수 있으며, 우주인의 장갑이나 우주복으로도 확장할 수 있다고 말했다.

연구진은 환자들이 이 시스템을 널리 활용할 수 있도록 기술을 더 발전시키고 의미 있는 감각정보를 장애인에게 더 잘 전달하는 방법을 연구할 계획이다.

존스홉킨스대는 로봇 손 분야의 선구자이다. 이미 10여 년 전에 대학의 응용물리학연구소가 장애인이 이전에 자신의 팔과 손을 통제했던 근육과 신경으로 로봇 손을 작동하는 기술을 개발했다.

원문은 다음과 같다.

Bringing a human touch to modern prosthetics

'Electronic skin' allows user to experience a sense of touch and pain; 'After many years, I felt my hand, as if a hollow shell got filled with life again,' amputee volunteer says

By Amy Lunday

Amputees often experience the sensation of a "phantom limb"—a feeling that a missing body part is still there.

That sensory illusion is closer to becoming a reality thanks to a team of engineers at Johns Hopkins University that has created an electronic skin. When layered on top of prosthetic hands, this e-dermis brings back a real sense of touch through the fingertips.

"After many years, I felt my hand, as if a hollow shell got filled with life again," says the amputee who served as the team's principal volunteer. (The research protocol used in the study does not allow identification of the amputee volunteers.)

Made of fabric and rubber laced with sensors to mimic nerve endings, e-dermis recreates a sense of touch as well as pain by sensing stimuli and relaying the impulses back to the peripheral nerves.

"We've made a sensor that goes over the fingertips of a prosthetic hand and acts like your own skin would," says Luke Osborn, a graduate student in biomedical engineering. "It's inspired by what is happening in human biology, with receptors for both touch and pain.

Image caption: Luke Osborn interacts with a prosthetic hand sporting the e-dermis

IMAGE CREDIT: LARRY CANNER / HOMEWOOD PHOTOGRAPHY

"This is interesting and new," Osborn adds, "because now we can have a prosthetic hand that is already on the market and fit it with an e-dermis that can tell the wearer whether he or she is picking up something that is round or whether it has sharp points."

The work, published online in the journal Science Robotics, shows it's possible to restore a range of natural, touch-based feelings to amputees who use prosthetic limbs. The ability to detect pain could be useful, for instance, not only in prosthetic hands but also in lower limb prostheses, alerting the user to potential damage to the device.

Human skin is made up of a complex network of receptors that relay a variety of sensations to the brain. This network provided a biological template for the research team, which includes members from the Johns Hopkins departments of Biomedical Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Neurology, and from the Singapore Institute of Neurotechnology.

Video: American Academy for the Advancement of Science

Bringing a more human touch to modern prosthetic designs is critical, especially when it comes to incorporating the ability to feel pain, Osborn says.

"Pain is, of course, unpleasant, but it's also an essential, protective sense of touch that is lacking in the prostheses that are currently available to amputees," he says. "Advances in prosthesis designs and control mechanisms can aid an amputee's ability to regain lost function, but they often lack meaningful, tactile feedback or perception."

That's where the e-dermis comes in, conveying information to the amputee by stimulating peripheral nerves in the arm, making the so-called phantom limb come to life. Inspired by human biology, the e-dermis enables its user to sense a continuous spectrum of tactile perceptions, from light touch to noxious or painful stimulus.

The e-dermis does this by electrically stimulating the amputee's nerves in a non-invasive way, through the skin, says the paper's senior author, Nitish Thakor, a professor of biomedical engineering and director of the Biomedical Instrumentation and Neuroengineering Laboratory at Johns Hopkins.

"For the first time, a prosthesis can provide a range of perceptions from fine touch to noxious to an amputee, making it more like a human hand," says Thakor, co-founder of Infinite Biomedical Technologies, the Baltimore-based company that provided the prosthetic hardware used in the study.

The team focused on developing a system capable of detecting object curvature (for touch and shape perception) and sharpness (for pain perception).

The team created a "neuromorphic model" mimicking the touch and pain receptors of the human nervous system, allowing the e-dermis to electronically encode sensations just as the receptors in the skin would. Tracking brain activity via electroencephalography, or EEG, the team determined that the test subject was able to perceive these sensations in his phantom hand.

The researchers then connected the e-dermis output to the volunteer by using a noninvasive method known as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, or TENS. In a pain-detection task the team determined that the test subject and the prosthesis were able to experience a natural, reflexive reaction to both pain while touching a pointed object and non-pain when touching a round object.

The e-dermis is not sensitive to temperature—for this study, the team focused on detecting object curvature (for touch and shape perception) and sharpness (for pain perception). The e-dermis technology could be used to make robotic systems more human, and it could also be used to expand or extend to astronaut gloves and space suits, Osborn says.

The researchers plan to further develop the technology and work to better understand how to provide meaningful sensory information to amputees in the hopes of making the system ready for widespread patient use.

Johns Hopkins is a pioneer in the field of upper limb dexterous prosthesis. More than a decade ago, the university's Applied Physics Laboratory led the development of the advanced Modular Prosthetic Limb, which an amputee patient controls with the muscles and nerves that once controlled his or her real arm or hand.